ABOUT JOHN: Upcoming Shows - Recent Shows - New Films - 300 Films since 1968 - Biography

John Porter Super-8 Idealist

by Peter Rist

Vanguard Magazine - April/May 1986, Canada

(digitized in 2007 by Fringe

Online)

Currently, in 2007, Peter

Rist (Ph.D., New York University, 1988) is

Chair of the School of Cinema, Concordia University, Montreal, Quebec.

![]()

Super-8 as a distinctive medium in experimental filmmaking has not been acknowledged in critical theory; its acknowledgment is in the work of the filmmakers. "These films don't exactly write their own theory, they substitute for it in its absence" says Peter Rist. In this singular examination, Rist, a teacher of film at the University of Western Ontario, focusses on the work of John Porter which aspires to produce exciting, moving images and draws attention to the specificity of his chosen medium, Super-8.

Just at the point where Super-8 filmmaking is being superseded by videotape as the low-cost format, its distinctive properties are finally beginning to be acknowledged. The lack of interest in the "narrow gauge" medium by writers on film is underlined by the fact that this acknowledgment is to be found in the work of film' makers rather than in film criticism or theory. One of the few critics who has shown an interest in 8mm and Super-8 film is Jim Hoberman. He notes that "Its history and development are... still very much a subject for further research," and his formulation of traditions that are peculiar to the "narrow gauge," found in an introduction to the work of Vivienne Dick, is still virtually the only serious attempt to come to terms with 8mm/Super-8 in a theoretical/historical way. 1 In this, Hoberman locates four categories of film that he finds to be both prevalent in and appropriate for narrow gauge: film practice: (1) "diaristic home movies and/or vacation films"; "documentation by the walker in the city"; "ironic spectacle" and (4) "confessional–psychodrama". He claims that the first is the most conventional - 8mm is traditionally associated with amateur, home-movie making - and points to the suitability of a portable and inconspicuous (because small) camera for the second type. The "irony" of the third is generated because the "film-maker's visionary ambition is continually played off against the paucity of his or her means." Hoberman again singles out an "extreme poverty of means" as being characteristic of the most important films in the fourth category (made by Vito Acconci), as well as remarking on an "insistent rawness of action and behavior." Thus, while he explicitly organizes narrow gauge films into genres, he argues implicitly that these particular types of film are significant because of the ways in which they are appropriate to the medium, particularly in their low cost.

Hoberman's theoretical thrust is polemical. He is arguing for the very existence of 8mm/Super-8 films and therefore he looks for things that distinguish them from other films. He has elevated the impoverished format in claiming artistry for those works that exploit its peculiarities. In this light Hoberman's approach is a traditional one not unlike that of silent film theorists Arnheim and Balazs whose arguments were predicated on considerations of cinematic "essence" wherein film was distinguished from the other arts, particularly theatre, and where its artistry was connected to the way it departed from reality. 2 This "modernist" stance has been superceded in the arts by a "post-modernist" one, but the notion is suggested here that it is probably necessary for theory of all new art mediums to pass through a "modernist" phase in order for the apparent nature of the medium to be defined. 3

Ironically, silent film theory blossomed just as sound was introduced so that it played a descriptive role rather than a normative one, and Hoberman's work appears to be in the same situation. With video threatening to usurp 8mm/Super-8's position, this theorist is better placed to describe existing work rather than to prescribe developments. Nevertheless, the narrow gauge film medium is not yet dead and some films by John Porter provide examples, along the lines of Hoberman's model, of ideal usage for Super-8 equipment. Though these films don't exactly "write" their own theory they substitute for it in its absence. 4

John Porter belongs to the Funnel collective of independent (mostly Super-8) filmmakers which began operation in Toronto in 1977. Porter was born in 1948. He made his first film, on Super-8, in 1968. From 1969 to 1974 he studied 16mm production at Ryerson Polytechnic Institute, and in 1975 branched out to study cartooning, illustration and ballet. Since 1974 he has made over 150 films, most of which he places in two different series. The first, begun in 1976, is called Condensed Rituals.

Landscape (1977) often introduces this series. It is one minute long when projected at 18 frames per second (fps) and consists of a pixillated single take showing the filmmaker and his mother painting in the countryside. An extremely tranquil afternoon is transformed into a frantic one, much more in keeping with city life than a country retreat. The obvious condensation is achieved through time-lapse photography while transformation of the "ritual" renders it comic. In terms of technique (pixillation) and effect (comic), the work can be compared to that of Norman McLaren, the seminal figure in Canadian animation. More interestingly, however, one can reflect after watching Landscape that part of the reason for the condensation could have been financial. Seemingly, the filmmaker posed himself the question of how to make a film of an afternoon in the country with just one cassette (3 minutes approximately) of Super-8 film.

The earlier Santa Clause Parade (1976) is five and-a-half minutes long when projected at 18 fps and consists of just three shots. The time lapse used between frames was three seconds. The camera was positioned high on a building looking down on a major intersection in Toronto. Crowds are shown to be gathering and police block traffic on the cross-streets. The parade moves from the top of the frame (in the background) towards the intersection, at which point it turns to the right of the frame and exits. Then the crowd disperses and the lens zooms-out. Traffic begins to move across the intersection again. The flow of people in the dispersal seems to move from back to front matching the movement of the parade.

As with Landscape, a comic effect is achieved by speeding up the movement. But here the great distance from the action impersonalizes it and places the emphasis on a design of people in motion, not unlike Buster Keaton's Cops (1922) and Fritz Lang's Metropolis (1926), wherein people are imaged as being machine-like on a grand scale. However, one could equally argue that they appear to be more like ants than components of a huge machine, in which case an analogy with a film such as Hilary Harris' Organism (begun in 1974) and the better-known Koyaanisqatisi (1982) is more apposite. 5 Harris' film compares pixillated, extreme-long shot views of city traffic with blood coursing through veins seen under a microscope, and his holistic schema casts a positive interpretation on the wide scope of (chaotic) human movement.

The tendency towards abstraction is continued in Amusement Park (1978/'79). Various camera set-ups depict different combinations of two or three rides filmed primarily at night so that the coloured lights are seen clearly. Though a shorter time lapse is used here than in any of the previous films – one frame per second – the speed of the thrill machines is such that the impression on the audience is a dizzying one. Typically, groans mix with laughs as the viewers question the sanity of partaking in this particular "ritual." In its last shot, Amusement Park attains a complexity absent in other of the Condensed Rituals. The combined comic and visceral emotional response continues into an extreme-long shot view of the midway, but the Brakhage- and Menken-like play of lights and colours finally commands the viewer's attention. 6 The multiplicitous loci traced by the many and varied rides also allow for a choice of what to look at, and appreciation of the sequence/shot is further enriched by the changing of the light and colour. The shot was filmed at dusk and as the sky darkened the aperture was widened. But Porter continued to manipulate the exposure so that the light intensity of the film increased as the natural light decreased. Colour is bleached out of the lights as the image gradually turns to yellow and eventually to white.

If Amusement Park is the most complex of Porter's Condensed Rituals, then the more recent Drive-In Movies (1981) most obviously satirizes North American culture. Parades and amusement parks - though profoundly American - are common to other cultures, but the drive-in is still peculiarly American. Porter reduced his presence in this film - there is less cutting and no changing of exposure - and returned to the simplicity of pixillated observation. Cars are seen to arrive extremely early, and as dusk falls the shadow of a screen below the camera stretches up to the centre of the frame, even revealing the movements of the "camera operator" (Porter) dashing from side to side in shadow above this. The viewer's eye is drawn to another screen (within the screen) where a James Bond movie is playing. This can be seen in toto, albeit at a number of shots per second, and an amusing impression is gained that this might be the best way to view such a film. But Drive-In Movies' real coup is saved for the end, when the cars are shown to depart. They appear to engage in battle recalling Weekend (1967), Jean-Luc Godard's satire on the predominance of the automobile in ritualized middle class life. To underscore drive-in park as battlefield, one or two stragglers remain at the end.

No single Condensed Ritual is quintessential. Each film is humorous and satirical in its own right, and some are stunning to look at, but when seen in a group the collective bombardment of imagery is highly suggestive of a "madness" inherent to modern North American society. On the one hand, the pace of life is revealed to be insanely fast through the filmmaker's choice of time lapse photography; on the other hand, participation in the rituals depicted is shown to be a "waste of time": an interpretation that is in part drawn from this same rapidity of action reducing the length of elapsed time by an absurd degree. In fact, by seeing a number of Porter's films together the existence of duration as a principal concern becomes quite evident. One is, of course, reminded here of Andy Warhol's film project. Whereas with Warhol the fact of duration is painfully imparted to the audience through exaggerated extension, with Porter the opposite procedure of extreme ellision ultimately encourages a similar response. Not coincidentally, the fixed camera is a central feature of Porter's style as well as Warhol's, and this connection points to a consideration of the Canadian's work as "structural." 7

But, though Condensed Rituals are to some degree "about" duration and the frame (in its fixed positioning) they are much more centrally "about" Super-8. In almost every case, a shot in a Porter film is a cassette in length. On viewing a collection of his films one is led to think about this fact, to acknowledge the practical aspect of the filmmaker's choice here, but also to understand the implications of cost. He is able to capture an event, a ritual, on an inexpensive cassette of Super-8 film. Though he neither in person nor in print argues this point, there is surely an implied polemic imbedded in the structure of these films, which holds that if one is poor one can still strive to realize, for example, something like Robert Altman's intentions in his body of satirical films, but in the format of Super-8, at a fraction of the cost. Porter is not attempting to create a work on an epic scale like the Kuchar brothers and the Bs, but his Condensed Rituals are similarly "ironic spectacles" and fit Hoberman's third narrow gauge genre in an original way.

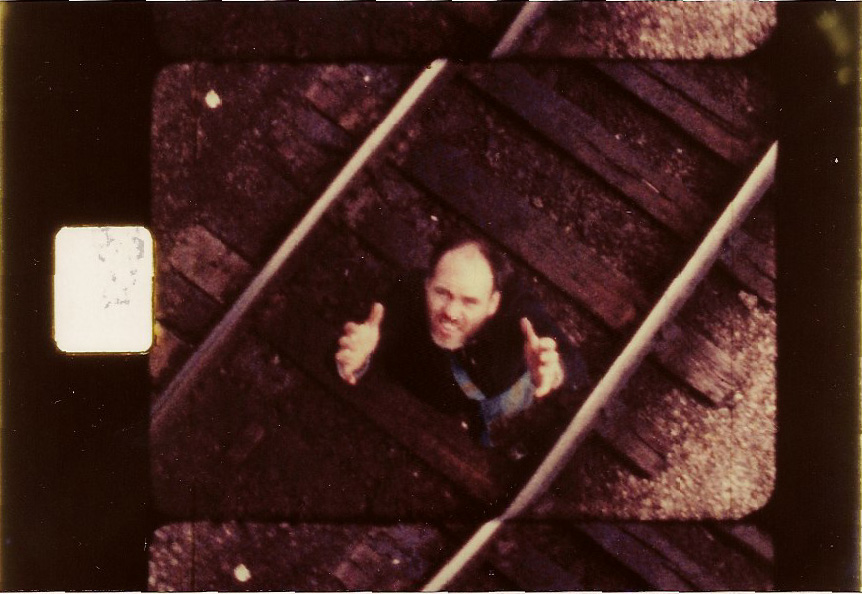

The second series of films, Camera Dances, contains works which are dances created on the screen from choreographed camera movement. Included are some live performance pieces - dancing with the projected light. Among those made in 1979 is Angel Baby (two minutes at 18 fps) which Porter claims was inspired by McLaren's Pas de Deux (1967). An aspect of this influence is McLaren's subject, dance. Porter was once a dancer, and in Angel Baby he performs for the camera providing the illusion in the second half of the film that he is flying. The camera was mounted in the ceiling of a room looking vertically down at the floor, which was covered in a blue carpet. But, this construction is concealed from the viewer until the end. Initially, Porter enters the film frame from the bottom left-hand comer as if he is walking on all fours. He is actually lying down on the carpet on his side. Among the moves that he makes that appear to be impossible are turning around full circle in the middle of the frame and climbing up to the upper right-hand corner. In Angel Baby, Porter continues to employ pixillation which enables him to both mask some of his unnatural movements and to imitate the look of McLaren's film. When Porter moves his arms and legs they blur like the edges of the dancers' figures in Pas de Deux. To reveal his trick, after he exits frame right in the illusory position, he returns standing upright and turns his head to look up at the camera, waves and walks off.

Angel Baby, though an early example, is typical of the best work in the Camera Dances. Firstly, the concept of Super-8 cassette as the standard is carried over from Condensed Rituals. Secondly, the filmmaker not only places himself as the subject of the film but also exaggerates this position by putting himself directly centre-frame. Here, possibly, Porter is drawing audience attention to the highly personal nature of these films, their "one man show" aspect. Finally, Angel Baby is characteristic in that it presents a puzzle for the viewer. One is intrigued by how the film is actually being made and a normal response to this is to try and figure out the mystery. At the end, Porter reveals the film's structure much like Michael Snow does in Presents (1981) where the camera tracks back away from the body of a truck to show that a strangely distorting set had in fact been moving back and forth, not the camera.

Cinefuge (1979/'81) a sound film, four-and-a-half minutes long, and the silent Down On Me (1980/'81), four minutes at 18 fps, are two of Porter's most significant works. Cinefuge presents the most fascinating puzzle of all of his films, and the trick of its making is not revealed in the film itself. The filmmaker, however, wishes the spectator to know how it was made since he provides details in accompanying programme notes. The film transport motor was locked-on. The camera was attached to a wire and Porter swung it around himself while turning on the spot. The length of the wire was selected so that the lower body of the cameraman would be cut off by the frame edge, enabling the fact that he was basically stationary to be concealed. The image on the screen shows Porter apparently in distress and being thrown around on the edge of an invisible centrifuge. The background whirrs by at a dizzying pace. Cinefuge is divided into three parts. The first consists of three shots, each one lasting as long as a line of advertising for the Funnel theatre. Porter leans back at times and the camera height above the ground varies providing a waviness and posture suggestive of him standing on a carousel. The effect is extremely amusing – if he was really on such a ride the centrifugal force would surely throw him off. In the second (single take) part a woman pops up into the frame and runs around the filmmaker in the same direction as the camera movement. This breaks the illusion that he is standing on the edge of a carousel but doesn't provide the answer to the riddle. Also, Porter himself is shown to turn around. Here he must have passed the wire about himself, continuing to throw out the camera, while turning around on the spot. The third section also consists of a single shot in which the final mind-boggling "camera dance" is performed by the filmmaker. As he swings the camera around him, Porter turns the camera about its own axis. One can observe that, whereas in the previous scenes Porter held his hands high apparently manipulating the camera with two wires, here he holds on to one, with hands placed centrally, and is able to rotate the camera first in one direction and then in the other. The effect on the screen is that the entire image tips upside-down while the blistering swish-panning of the background past Porter is unabated. The illusion of inexplicable flight is enhanced by the filmmaker's gasping oohs and aahs which comically understate the apparent thrills.

Similarly, Down On Me (1980/'81)

does not reveal its technique. But again, Porter tips his hand in the

accompanying programme notes:

"Wanting to film himself from the viewpoint of a falling camera,

the film-maker threw a camera, running at normal speed, up in the air

on a small parachute. The resulting film was too blurry and abstract

so a camera, running at one frame per second, was tied to the line of

a fishing pole. A friend stood with the pole at the top of roofs, bridges

and staircases, slowly raising and lowering the camera while the film-maker

posed at the bottom."

There are a number of shots in this film and the length of it continues to expand as Porter finds more locations to shoot from. Each shot/location is linked by a matching of vertical camera angle - the camera functions as a plumb bob and so the lens axis forms a perfect right-angle to the ground, camera movement - also vertically downward, and the position of the subject/ filmmaker - centrally framed, looking up. 8 In each location the camera moves down at Porter in rapid pixillation and moves past him to be faded out as it reaches the ground. Then the movement is reversed as the camera is reeled back up to its starting point. On the screen, the image of the location turns around, since the camera rotates at the end of the fishing line. Porter, looking at the camera, was able to watch this motion and turn himself in sequence. Thus he appears not to move at all while the location - usually a stairwell - spins around him. As the film progresses, the speed of axial line movement as well as its rate of spin increase so that Down On Me concludes in a dizzying whirl. The colour contrast between one "scene" and another is striking and at times there is a noir effect because of an extreme lighting variation in a stairwell where the camera's target appears to be cellar-like. In the last of these sequence/shots, Porter seems to be standing in a triangle of light and as the camera approaches him the illusion of afterimage caused by pixillation evolves into flickering overlays of white star shapes on black. Here it is almost impossible to believe that such a stunning effect was achieved in the camera and that Porter didn't resort to optical printing or superimposition of some kind.

All of Porter's films provoke an emotional response, at its strongest in Cinefuge and Down On Me. For those who wish to argue that a physical effect can be imparted by films these two provide excellent illustrations. 9 Both are truly dizzying, an impression which is made all the more remarkable when one considers that they were made in the home-movie format of Super-8. Larger-scale image – 70mm, and sound – Dolby stereo, are technological advances that naturally equate with the modem day rise of the "visceral" factor in Hollywood movies, so that Porter's actual achievement of "spectacle" with smallness allows these films to transcend the "irony" that Hoberman associates with the work of narrow gauge filmmakers whose intentions reach beyond the medium's capabilities. Down On Me, in fact, strongly alludes to Vertigo (1958), a key Hollywood film in terms of visceral affect. Hitchcock's tour de force builds its vertiginous effects through a pulsating soundtrack, swirling imagery – including the nightmare of the central character, Scotty, and his car rides up and down the hills of San Francisco—and most importantly, the combined zoom and track in different directions that marks the protagonist's affliction with acrophobia. 10 The desire to fall working against a fear of falling meaningfully structures the whole of Vertigo and Porter, in Down On Me, translates this pull/push, attraction/repulsion aspect in an even more physically engaging, emotionally moving way than the zoom/track dichotomous device that the former Hollywood master of audience manipulation designed.

Porter's Camera Dances are related to Hoberman's "psychodrama" and "home movie" narrow gauge genres through the extreme centrality of the filmmaker himself as subject. They also work as "ironic spectacles," but most strikingly they fit the "walker in the city" genre by way of the portability of the Super-8 camera. That Vivienne Dick's films represent all the Super 8 genres signified their importance for Hoberman; the same claim can be made for Cinefuge and Down On Me. Nevertheless these films are most remarkable for their expansion of the possibilities inherent in the lightweight nature of narrow gauge equipment only suggested by "walker in the city" films. Thinking of how manageable Super-8 cameras can be, Porter has dreamed up camera moves that would be unimaginable in any other format. Primary is the procedure of remote-controlled camera operation. But the camera now has been freed from its fixed position, virtually being given a life of its own, albeit a tenuous one, hanging by a thread in one film to the fishing rod operator and in the other to the filmmaker. Ironically, against this "freedom", the focus is severely restricted as Porter turns the camera away from the world at large of Condensed Rituals, inwardly onto himself. This irony is compounded in the dichotomy between the way the films were made and how they appear on the screen. In the former it is the camera that flies, that is free, but in the latter case it is Porter who appears to fly. The works are structured by another split: the filmmaker's dual purpose of (a) attempting to produce magic - the illusion of flying, and exciting, moving images, and (b) acknowledging and drawing attention to the specificity of his chosen medium - Super-8.

Porter may not be present in some films, but as performance works they require his presence for their existence. In a mini-series of Camera Dances called Scanning, Porter holds a Super-8 projector in his arms and scans the screen with the projected image. The scanning repeats the moves that had been made with the projected image. Scanning (1981), Scanning 2 (1982) and Scanning 5 (1983) consist of a single shot. In the first, Porter begins with his projection at the top left-hand comer of the screen. The image shows the corresponding corner of a warehouse-like building. He tilts down to the ground, tracks slightly to the right and tilts up to the top. This move is repeated until the whole building has been covered. On the last pass, his fellow filmmaker Jim Anderson is revealed, standing on the sidewalk. Brilliantly, for Scanning 5, Porter breaks the bounds of the projection surface, the screen, following a right pan around a side wall to keep a man in frame who walks in this direction. Amazingly, Porter swings his projector up to the ceiling following the camera's tilt to the sky and with the audience craning their necks to view the film from underneath, the same man breaks back into the frame, looking directly down at the camera, Porter, and hence the audience.

Like Cinefuge and Down On Me, the Scanning series both entertains and enlightens. It extends Porter's interest in the portability of Super-8 equipment from recording devices to projectors. It would be possible, I suppose, to carry a 16mm projector while screening a film, but very inconvenient. Discounting weightlifters, it would be impossible for anyone to adapt this procedure to 35mm film. Thus Porter has again discovered an appropriate strategy for the narrow gauge medium. But also, in so doing he has opened up a whole new area for films made with creative projection in mind. Again, as in many of his films, he works out of the idea of the cassette as the basic unit of Super-8 film, emphasizing the "paucity of means" that through his work has become a central "structural" element of his chosen format. Scanning 1, 2 & 5 are single-shot films, approximately the length of a cassette. But Porter has moved away here from the project of exploring remote control and pixillation, although he continues the tendency of Camera Dances to focus on the personality of the filmmaker.

Unless he trained a projectionist to show the Scanning series film by film, Porter would have to appear in person in order to do this. He has thought of a strategy that demands his presence at the projection stage. Though this reads like an affirmation of Porter’s ego, in fact, it seems to me that he conceives of his presentations of his own films as “shows” and social gatherings (rituals?). It has become commonplace for avant-garde filmmakers to be present at screenings of their own films (often to explain them). In Porter’s case, he seems to want to be there to solve the puzzles he presents with his illusory works and he virtually has to be for his performances. This is particularly appropriate for Super-8. The format is, after all the quintessential amateur, home-movie medium and Porter continues this tradition by making himself a central part of his performance.

NOTES

1. J. Hoberman, "A Context for Vivienne Dick," October 20 (Spring, 1982):102-104.

2. For example, on "departure," Arnheim notes that film technique, rather than simply being a mechanical reproduction of nature, actually forms the tools of the creative artist (first printed in "Film als Kunst", 1933). Rudolf Arnheim, Film as Art (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1957); 127. See also, Bela Balazs, Theory of the Film (New York: Dover, 1970 1952). Here, Balazs explains the development of film out of theatre in "Ancient History," only to separate the two art forms in the next chapter, "A New Form-Language."

3. The roots of material theory go back, of course, to Lessing's "Laocoon," published in 1766 (and both Arnheim and Balazs recognize this seminal work), but I consider the term "modernism" to mark the most extreme stage of this tendency, where the "artist" works in full consciousness of his/her medium. "Post-Modernism" I consider to be coincident with post-Wittgenstein, in the sense that he was against the concept of "essences." The most important argument along this line in the realm of aesthetics has been propounded by Morris Weitz. See "The Role of Theory in Esthetics" in a Modern Book of Aesthetics, ed. Melvin Rader (New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1979).

4. See Noel Carroll, "Avant-garde Film and Film Theory," Millenium Film Journal, Nos. 4/5 (Summer/Fall 1979). In this article, Carroll effectively argues that films can't actually create "theory" though they can "provoke theory change." p.137. He continues: "A given avant-garde film can serve as counter-evidence or as a counterexample to existing theories by manifesting a possibility or aspect of the medium hitherto ignored by theorists. In this role, the avant-garde film operates as a piece of new data that forces theory to expand its analytic framework in order to assimilate it." I believe that Porter's films fit this description.

5. Porter's typical Condensed Rituals look most like a series of "blitz" films made for the French language CBC network in 1976, Les Interludes, directed by Roger Cantin and Jean Claude Berger. Brakhage's earlier work in this area, I'm thinking particularly of Night Cats (1956) and Anticipation of the Night (1958). Menken's key film, Notebook, though not completed until 1962, was seen in part by Brakhage well in advance of this.

7. I am primarily thinking of Sitney's definition here, in as much as he considers Warhol to be the first "structural' filmmaker and since he includes "fixed camera position (fixed frame from the viewer's perspective)" as one of the "four characteristics of the structural film…” Sitney, p. 408.

8. I feel that each sequence seems like a single shot (hence my term “location/shot”) because the ground blots out the lens on the down pass. The idea that an object getting in the way of the camera can mask (through a fade-out, then fade-in) the act of editing began with Hitchcock’s Rope (1948).

9. I am thinking here of the Soviet and East European theorists/directors, in particular Kuleshov, Vorkapich and the early Eisenstein (with his elements of “affect”).

10. For an introduction to this approach, see Robin Wood, Hitchcock’s Films, 2nd ed. (New York: Castle Books, 1969), 71-97.

![]()

John's Upcoming Shows - Recent Shows - New Films - 300 Films since 1968 - Biography